The Golden Circle is a popular sightseeing route in south Iceland. But it isn’t just a route—it’s an immersive dose of what makes Iceland so unforgettable: fire and ice, myth and geology, chaos and silence. It brings you face-to-face with some of the island’s most iconic landscapes and elemental forces. Here, the earth splits beneath your feet, geysers explode into the sky, and waterfalls thunder through ancient canyons. But it’s not just a scenic checklist—it’s a kind of initiation. A journey through a place that still seems to be forming itself, moment by moment.

Despite its popularity, the Golden Circle holds moments of deep stillness and wonder. And while many travelers do it in a single rushed day, we’ve chosen to slow down, to spend the night in its embrace.

Our day began at the Ion Adventure Hotel (www.ioniceland) perched dramatically on the edge of Iceland’s volcanic wilderness. We had arrived the evening before, checking in just as the daylight softened into dusk. Over a quiet dinner in the hotel’s minimalist restaurant, we eased into the stillness of the landscape, the geothermal steam rising in the distance like a reminder of the raw power beneath our feet.

Thingvellir National Park. http://www.thingvellir.is

We were grateful that Kristinn allowed us a gentle start to the day—time to recover from the previous afternoon’s subterranean adventures. We departed the hotel at a leisurely 9:30 a.m., which felt like a small luxury, a quiet gift of recouperative time amid the rhythm of our journey.

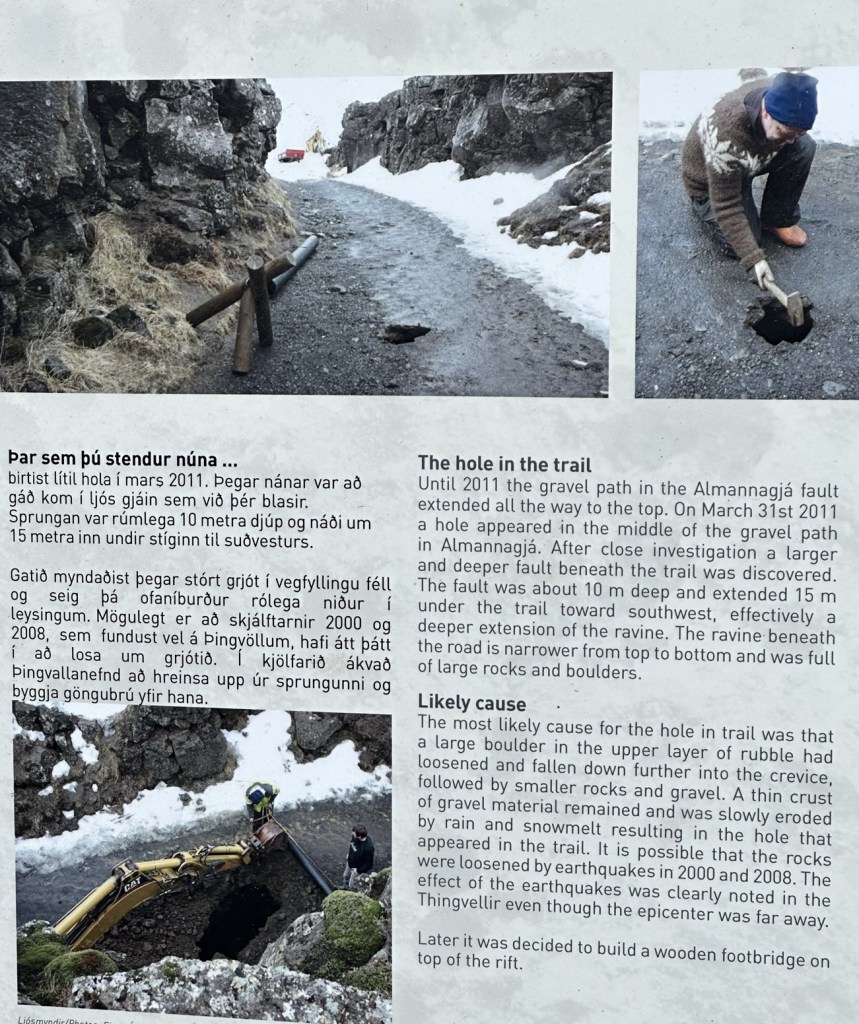

Our first stop was Thingvellir National Park, a place where geology and history collide—literally. Here, the North American and Eurasian tectonic plates pull away from each other, tearing open the earth at a rate of about 2 centimeters per year. We walked along the Almannagjá rift, flanked by towering walls of volcanic rock, as if through the spine of the continent itself.

Thingvellir isn’t just a geological marvel—it’s also the birthplace of the Alþingi, Iceland’s national parliament and the oldest surviving parliament in the world, founded in 930 AD. Back then, Viking chieftains would gather here once a year to settle disputes, recite laws, forge alliances, and probably passive-aggressively glare at their enemies across the lava plain. It was Icelandic democracy in its earliest, coldest, and most outdoorsy form.

Standing there, between continents, I felt a quiet awe—not just at the scale of the landscape, but at the weight of history embedded in the stones beneath our feet. It’s rare to find a place where the earth quite literally opens up, inviting you to witness both its inner workings and the echoes of ancient human gatherings. There was something humbling in it all: the jagged cliffs, the slow-moving plates, the voices lost to time. I left Thingvellir feeling smaller—but also more connected, as if we’d touched something elemental that morning.

Laugafvatn Fontana

Some people go to spas for facials and massages. In Iceland, you go to the spa and end up baking bread in a volcano.

Well, not in a volcano exactly—but close enough.

We continued on to something altogether warmer and more delicious: the geothermal bakery at Laugarvatn Fontana.

Nestled beside a steaming lake, this modest but fascinating spot is known for an old Icelandic tradition—baking rye bread in the hot earth itself.

Our guide, Pilibe, greeted us with the calm enthusiasm of someone who knows he’s about to blow a few minds with a loaf of bread. He walked us down to the edge of the lake, where the black sand steamed faintly under our feet.

“This,” he said, patting the ground, “is our oven.”

Pilibe, our rye bread guru, stood beside a steaming patch of black sand and explained the ancient-meets-modern alchemy behind Iceland’s most grounded delicacy.

“The recipe is simple,” he said. “Rye flour, buttermilk, baking soda, sugar… and patience.”

He held up a metal pot, and sealed it tight in what looked like half a roll of plastic wrap. Once the dough is poured in, the whole thing is buried in the hot sand—no oven, no dials, no apps—just the natural rhythm of the earth doing the baking. After twenty-four hours, presto: perfectly moist, sweet rye bread, cooked by the planet herself.

Then, in the same calm tone, Fabrizio added, “And please… do not stick your fingers into the ground. You will burn them off.”

We laughed—nervously—and kept our hands respectfully to ourselves.

Because apparently, baking with lava heat comes with a side of respect for mortality.

It sounded like something from a fairy tale.

Pilibe asked for two volunteers— so without hesitation I volunteered Bud, who stepped forward to do the honors of digging up a pot left in the oven the day before. Never one to shy away from a moment in the spotlight (or a mysterious hole in the ground), Bud grabbed the shovel with theatrical determination. “Let’s see what’s cooking,” he said, as if unearthing Viking treasure. With gloved hands and some enthusiastic digging, he and a woman named Gail, reveal a small pot that had been buried the day before—sealed tight and slow-cooked in the natural heat of the earth, just Mother Nature running her own slow cooker. Pilibe, Bud and Gail, then buried another pot for the bread makers who followed.

Then, back in side for the tasting.

Pilibe popped the bread out of the pot, cut it into triangle pieces, and handed them out. The taste of Fontana rye bread is unlike any rye you’ve likely had before—dense, dark, faintly sweet, and wonderfully moist.

The rye bread was warm to the touch and slightly sticky on the surface. The flavor is deep and comforting—malty, almost caramelly, with a subtle tang from the rye. There’s no crust to speak of, just a smooth exterior that gives way to a richly aromatic interior. Served with a generous layer of Icelandic butter and a slice of smoky trout, it melted slightly on contact, turning each bite into something at once rustic and indulgent.

It was a quiet, grounding kind of treat—humble in appearance, yet born of fire, water, and time. In Iceland, even bread carries the memory of the landscape.

Haukadalur valley, Geysers

With warm bread still lingering on our tongues, we continued deeper into the Golden Circle toward one of Iceland’s most iconic geothermal sites: the Haukadalur valley, home to the famous geysers.

The landscape shifted again—steam rose from vents in the earth like wisps of breath, curling into the wind. The ground here is alive: bubbling mud pots, sulfur-stained rocks, and pools shimmering in impossible shades of turquoise and gold. The air smelled faintly of minerals and eggs, a scent we were beginning to associate with wonder.

We stood among a small crowd near Strokkur, Iceland’s most reliable geyser. Every 5 to 10 minutes, it gave a warning gurgle, then surged skyward in a magnificent column of scalding water—sometimes reaching 20 meters or more. The crowd gasped every time, no matter how many times it erupted. We watched from different angles, trying to catch the precise moment the dome of water ballooned and burst into the sky. I must admit, Strokkur had a faster draw than I did—each time I raised my phone, ready to catch the eruption, it was already mid-roar or fading into mist. The geyser always seemed to sense when I blinked or hesitated, launching skyward just before I hit record. I never quite managed to time it right, but in a way, that made it better. It forced me to not worry about filming and simply watch—steam rising, people gasping, the earth exhaling.

Nearby, the original Geyser—the one that gave all others their name—lay mostly dormant, breathing quietly beneath the surface. It felt like standing beside a sleeping giant, respectful of its rest, yet aware of its strength.

Gullfoss

From the geysers, we continued eastward until the landscape opened to one of Iceland’s most dramatic scenes: Gullfoss, the “Golden Falls.” Even from the parking lot, we could hear its thunder—a deep, steady roar that seemed to vibrate through the rocks. As we walked closer, the path curved along the edge of a gorge, and suddenly there it was: a double-tiered waterfall plunging into a narrow canyon, shrouded in mist and rainbows.

The volume of water is staggering, especially in summer when glacial melt feeds the Hvítá River. It crashes down with a force that feels ancient and unstoppable. We stood in silence for a moment, letting the spray kiss our faces and the sound drown out all thought. It was less like looking at a waterfall, and more like confronting a raw, beautiful force of nature.

No camera of any kind quite does it justice. You have to feel it—to watch the water fold over itself, disappear into the crevice below, and then reappear as rising mist. It’s a place where light and water collide, and time seems to slow.

Fridheimar

After the drama of Gullfoss and the roaring geysers of Haukadalur, we found ourselves in a place that was unexpectedly warm, quiet, and green: Fridheimar, a family-run tomato farm tucked just off the Golden Circle route.

Step inside, and you’re instantly wrapped in the gentle humidity of a greenhouse. Rows of vibrant tomato vines stretch toward the glass ceiling, their branches heavy with ripe fruit. Bees buzz lazily from blossom to blossom, pollinating by hand what nature once left to the wind. This isn’t just a farm—it’s a thriving ecosystem under glass, powered by geothermal heat and Icelandic ingenuity.

Now it was time for food. Following Kristinn’s sage advice and careful planning, we had reserved a later seating to avoid the tour buses and large crowds. It worked—we were seated immediately, not in the main greenhouse, but in a separate building where grapevines curled overhead and sunlight filtered through the glass. The atmosphere was warm and inviting, a gentle contrast to the wind outside. The menu, unsurprisingly but delightfully, revolves around the tomato in all its glory. I started with freshly baked bread and a bowl of bright red tomato soup. It was sweet, velvety, and surprisingly rich for something so simple. The tomato ravioli followed—a perfect way to honor such a humble fruit.

Outside, the Icelandic landscape is rugged and windblown. But inside Friðheimar, it’s summer every day.

Walk into the wild

After our tomato-based outing, we returned to the Ion Adventure Hotel, where I decided to take a walk—alone. I stepped out behind the hotel, started uphill, and turned left at the sign marking the trail. The sky had begun to shift—the clouds thickened, and the temperature dropped noticeably. I zipped my jacket and kept going.

The trail was steeper than I expected in places, carved into dark volcanic soil and slick with recent rain and crumbling volcanic rock. At one point, I had to grip a rope bolted into the rock to pull myself up a short, steep section. It wasn’t dangerous, just unexpected—and something about that effort, about pulling myself up that hillside alone, cracked something open in me.

As I walked, my thoughts drifted to decisions I’ve made over the years—the big ones, the ones that changed the shape of things. Some I’ve stood by without regret. Others… I’m still turning over, trying to understand their weight. There’s a clarity that comes with walking uphill in the cold, lungs working, hands cold, body alert. It leaves just enough room for the truth to surface.

I paused near the top, where the land opened up. The hotel was far below now, barely visible. It was quiet except for the wind. I pulled out my phone and recorded a short video for my granddaughter. I didn’t say much—just showed her the view, let the wind speak, and told her I was thinking of her. It wasn’t about the words. It was about being in that moment and wanting to share it with someone I love.

It wasn’t a long walk, just an hour. But it stayed with me.