An old Greek proverb says Απ’ το πουθενά, ήρθε το καλύτε, translated (by google, not me) “Out of nowhere, came the best.” This describes our day in the mountains of Crete.

Demetrius, our driver for the day, fetched us from the Phaea Blue in the afternoon. Demetrius is tall and broad-shouldered man, with a dark beard that frames a face marked by confidence and welcome. He exudes ease and a sense of familiarity with his surroundings — a local who knows every stone of the land beneath his feet.

He arrived in a well-worn Land Rover Defender—one of the classic models from before the 2016 redesign. Rugged, boxy, and built for the wild, it looked every bit the part with “Safari Experts” painted along the side. When we ask if there’s air conditioning, Demetrius grins and tells us to roll down the windows—we’ll be driving for just over an hour. We, the spoiled Americans, exchange skeptical glances, already picturing ourselves melting in the heat. But it turns out he’s right. The wind rushing through the open windows is more than enough. Demetrius offers a cryptic smile and says only, “Something special is coming.” We don’t know what he means, but we’re already leaning forward in our seats like eager beavers.

Our journey begins at a humble goat farm nestled in the hills, where we’re welcomed by a local farmer. We dip crusty bread into golden olive oil pressed from his own trees, learn the ancient rhythm of milling grain by hand, and share a quiet moment with Marguerite—the gentle goat who teaches us how to milk with patience and care.

We couldn’t resist picking up a jar of honey from the farmer—amber-colored, thick, and humming with the scent of wild thyme and sun. It felt like taking a little piece of the mountains with us. Unfortunately, the jar had other ideas. Somewhere along a bumpy road, it leaked all over my pack, turning everything inside into a sticky mess. The honey won’t be making it home, but I suppose that’s just part of the adventure.

We thank the farmer, and move on.

In the tucked-away village of Abdou, we met Antonas, our local guide, and his assistant, Manos (1 of 4 Manos we would meet that day). We gathered in a traditional taverna, owned by a man named George, and shared pistachio gelato and sipped Greek coffee beneath flowering vines. With the rhythm of the island in his voice, Antonas recounts Crete’s epic past—from Minoan kings and Venetian walls to Ottoman resistance and village uprisings. Antonas’ face bears the lines of generations, and his heart beats with the stubborn pride of an island that has never truly been conquered.

Abdou itself is a small, traditional village tucked away in the mountains of Crete, located on the southern slopes of Mount Dikti. This village is quiet and unspoiled by mass tourism, giving us a chance to experience the rhythms of rural Cretan life. Old stone houses covered in vines, narrow alleyways, and friendly locals define its charm. Some of the houses are in ruins, and others redone.

After our walk through Abdou, we piled back into the Defender and wound our way higher into the hills. En route, we stopped in a tiny mountain village where Demetrios needed to pick up a few supplies. While he ran his errand, I wandered across the street and discovered a roadside artist quietly working beside a scattering of painted gourds. His specialty? Painting on dried gourds. I couldn’t resist. I bought one painted like a giraffe for CJ, my granddaughter. It felt like the perfect bit of Crete to bring home.

Back in the Defender again, a few miles later Demetrius veered off paved road onto a very bumpy mountain one. Driving a mountain road in Crete is an experience both exhilarating and humbling—a winding journey through the island’s raw, elemental heart. The road clings to the mountainside like a ribbon, narrow and often without guardrails, twisting around jagged cliffs and plunging ravines. As we climbed higher, olive groves give way to rocky outcrops, wild herbs scenting the air—thyme, oregano, sage—released by the heat of the sun. Goats appear like acrobats on the edges of steep inclines, impossibly balanced, indifferent to your cautious passing. Hairpin turns demand full attention, and the pace slows. Occasionally, we passed a faded shrine—small white boxes with blue crosses—marking a memory, a miracle. The road narrowed further, sometimes to a single lane, as if inviting us to slow down, to surrender to the rhythm of the land. It is not a road to rush. It is a path that demands respect—and in return, it reveals the soul of Crete: untamed, timeless, and quietly majestic. Demetrius knows each and every bump and turn, at times quite the showman.

More and more goats appear along the way. Whether darting across sheer ridgelines or lazing in the shade of an olive tree, goats are both a living connection to Crete’s pastoral traditions and a vital part of its identity.

We’re told we’ll be visiting a shepherd, but the details are vague—intentionally, it seems. The road narrows to little more than a rocky path, and soon we’re bumping along through scrub and stone. At last, we stop at what appears to be a makeshift gate: concrete wire strung haphazardly between posts, knotted closed with a length of old rope. Without a word, Demetrios climbs out of the Defender and moves to “unlock” it—though it’s more an act of untangling than opening. There’s a quiet sense of anticipation in the air, as if we’re crossing into another rhythm of life entirely.

Once inside the gate, we’re met by a curious gathering of goats—some bold, some cautious—all watching us with wary eyes and twitching ears. They mill around the Defender, their bells clinking softly in the stillness. Off in the distance, we spot a scattered herd of sheep dotting the slope of the mountain, like woolly punctuation marks across the scrub. The air smells of thyme, dust, and animal warmth. We’ve clearly entered their world now.

But the best is yet to come. At the end of a crooked stone path leading to a humble rural house, Haralabis awaits us. He stands there with a quiet pride, holding a wooden tray bearing four small glasses of raki—the fiery Cretan spirit—and wedges of his handmade cheese, sharp and creamy from the milk of his goats and sheep.

Up random stone stairs behind him, as if conjured from the land itself, two musicians (both named Manos) begin to play. One cradles a lyra, the iconic Cretan string instrument, its sound high and mournful, like wind through mountain pines. The moment is unexpected, intimate, and utterly magical. We step forward, drawn in by hospitality that feels older than the stones beneath our feet.

This is a striking outdoor dining scene set high in the Cretan mountains. The table, made of rustic wood with a simple X-frame design, is long and communal, inviting shared conversation and slow meals. Two benches run its length, each topped with soft beige cushions that soften the sturdy look of the wooden planks.

The table is elegantly set with white plates, clear glasses, and sprigs of herbs—likely thyme or rosemary—in a small potted centerpiece. The light is golden and low: the sun is beginning to set over the distant ridgelines, casting long shadows from the benches and trees. The view is breathtaking—layered mountains rolling down and down.

There’s a peaceful, timeless feel here. You can almost hear the tinkling of raki glasses and the slow clink of forks, backed by the soft hum of Cretan music and warm conversation. It’s the kind of table where memories are made.

The entire scene is steeped in warmth, tradition, and hospitality.

We learn that Haralabis’ family has been tending goats and sheep in these meadows since the 1800s. The land, the rhythm, the way of life—it’s all been passed down through generations. Haralabis lives here alone now, among the stone walls and grazing hills, but he’s not entirely on his own. His son and grandson—Manos—still carry on the tradition. They come up from the village twice a day to milk the family’s goats and sheep, just as their ancestors did. There’s something deeply grounding in this quiet continuity, a living thread that ties past to present.

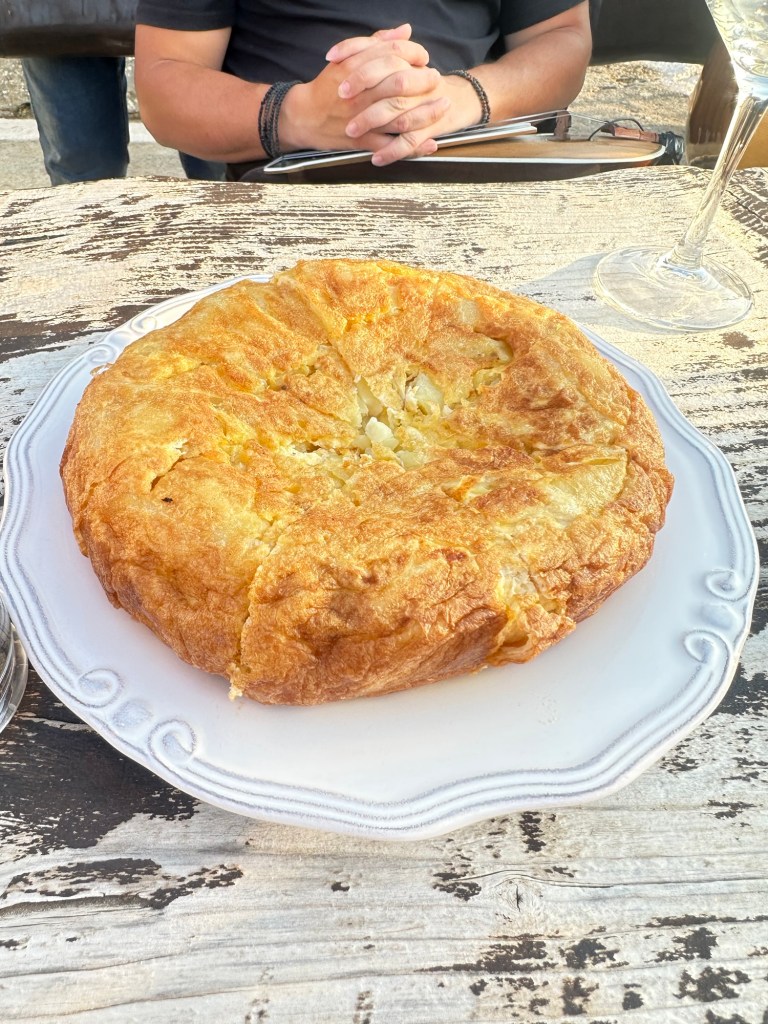

As the musicians begin to play, plates of food start to fill the table.

We leave the table for a short time as the sheep come down for milking.

We watch as the milking process unfolds—efficient, practiced, and almost meditative. Then, with a twinkle in his eye, Haralabis’ grandson steps into the herd and gently lifts a few lambs, handing them off to us one by one. “Take them home,” he says with a grin, as if we could simply tuck them into our backpacks and carry them back across the world. The lambs are soft, warm, and a little bewildered—much like us. The moment is both surreal and deeply human, a reminder that here, hospitality extends beyond raki and cheese—it includes a lamb, if you’re willing.

We return to the table to finish dinner, the last of the dishes passed between us. Conversation softens as the sun begins its slow descent behind the hills of the mountain. The sky turns honeyed gold, then deep rose, casting long shadows across the stone terrace. We sit in quiet awe, glasses in hand, watching the day melt into evening. It’s not just a meal—it’s a memory, etched in the light of a Cretan sunset.

At last, it’s time to leave. We climb back into the dusty Defender, the sky now inked with stars. On the long ride home, Demetrious plays classic Greek music the entire way—haunting, nostalgic melodies that seem to rise from the very earth we’ve just walked. No one speaks much; we’re all wrapped in the spell of the evening.

This has been an extraordinary night. From a crooked stone path and a tray of raki came something timeless and unforgettable. As in the old Greek proverb: out of nowhere came the best.