Our journey to Crete began at the Parikia ferry dock, on the western coast waterfront. It’s a bustling quay where large ferries and smaller high-speed catamarans come and go, without regard to anyone’s readiness. The crowd slowly builds as the departure time draws closer. News of a 30 minute delay in unwelcome, as people crowd into the port entrance to escape the beating sun.

Ferries don’t sneak in; they arrive like minor gods, announced by their own thunder: a horn blast, a churn of sea, a massive silhouette appearing where there had been only sky and horizon a moment before.

Our prior ferry experience reminds us not to toy with these gods — one dither or fumble may very well leave a wannabe ferry hopper expectedly dejected at the ferry dock. The calculus is rather simple: you move at ferry pace or you are out. Such is the case with Paul from London, who while boarding an earlier ferry, to another island with his wife and small children in tow, was left at the dock when he stepped off the ferry to retrieve his family’s remaining luggage. Left on the dock with neither his family, phone nor wallet (but am an ample supply of baby diapers), this unfortunate left Londoner could not remember his wife’s cell phone number. We had the pleasure of Paul’s company for several hours. This witty chap took everything in stride. We helped Paul with his bags getting onto the ferry and bid our goodbyes, pleased that he and his supply of baby diapers was safely on board to reunite with his family.

As the ferry pulls away, Parikia fades—a cluster of glowing houses, blue domes, and distant hills. The ferry picks up speed, skimming the water toward Crete, the largest island in Greece. We settle into our seats and as time passes there is not even a hint of a reason to check a watch. This beast will get to Crete on its own time.

After stops at Naxos and Santorini, we de-boat and spot our waiting driver at the ferry port in Heraklion Crete.

Crete looks vastly different than the other places we have been in Greece. The terrain here is dramatic: craggy mountains descend into gorges and olive tree-dotted valleys, while the coastline shifts between sheer cliffs and hidden coves with aquamarine waters. Olive trees are in spectacular abundance, one account placing the number at thirty six million. But who is counting. The island is located at the southernmost edge of Europe in the middle of three continents: Europe, Asia and Africa. Wonders lie ahead.

After about an hour drive, we arrive at the gates of the Phaea Blue, a resort on the eastern side of the island in Elounda.

As our car winds up the sunbaked entrance, remains behind the sea, like a sheet of glass streaked with silver. Nestled discreetly between a mountain range covered in olive groves and the Aegean, Phaea Blue doesn’t shout for attention—it whispers sophistication. No towering sign, no grand gate. Just a stone pathway lined with rosemary and lavender, and a staff member waiting with a smile and a chilled towel scented with orange blossom.

We step into a reception area that feels more like a private villa than a hotel—open to the breeze, decorated with handmade ceramics and pale linen. There is no check-in desk in the usual sense; you’re invited to sit, sip a herbal iced tea, and let the paperwork happen around you. The pace is slower here, more thoughtful. This isn’t just check-in—it’s entry into a different rhythm of life.

Our travels have brought us to many extraordinary hotels. This is one of them: but Phaea Blue is different, way different.

Our suite opens onto a private terrace carved gently into the coastal slope. A low wall of honey-colored stone wraps the patio, offering both shelter and openness. From here, you gaze directly over the bay, where the sea glitters like hammered glass and the Spinalonga Island (once a Venetian fort; a Muslim refuge; and then a leper colony, the subject of the book “The Island, by Victoria Hislop) rests on the horizon like a whispered story.

The plunge pool is sun-warmed and secluded, framed by native grasses and olive trees. In the morning, the sun rise is mesmerizing, and then you may float alone beneath a chorus of cicadas. In the evening, the setting sun turns the sky lavender and rose, the pool water spilling over coped blush white stone edges. Phaea Blue simply breathes with the sea.

It has been a long day of travel and we reconnoiter for a Phaea Blue dinner.

In the morning, we head out to another historical archaeological site. Just south of modern-day Heraklion, nestled among low hills and olive groves, lies the ancient Palace of Knossos — the legendary center of Minoan culture, Europe’s first advanced civilization, daring back almost 5,000 years. Stepping into Knossos is like walking into myth: a place where archaeology and storytelling are forever intertwined.

Our local guide Maria is as frustrated as we are when a throng of visitors from two large cruise-ships pile in. We skip several key attractions when we see lines that would soak up our precious time. Still, our outing was worthwhile.

We ended our day with Maria at the Heraklion Archaeological Museum, the crowds building behind us. Maria skillfully directs us from one important artifact to another, mindful of the need to depart before the flood of people arrive.

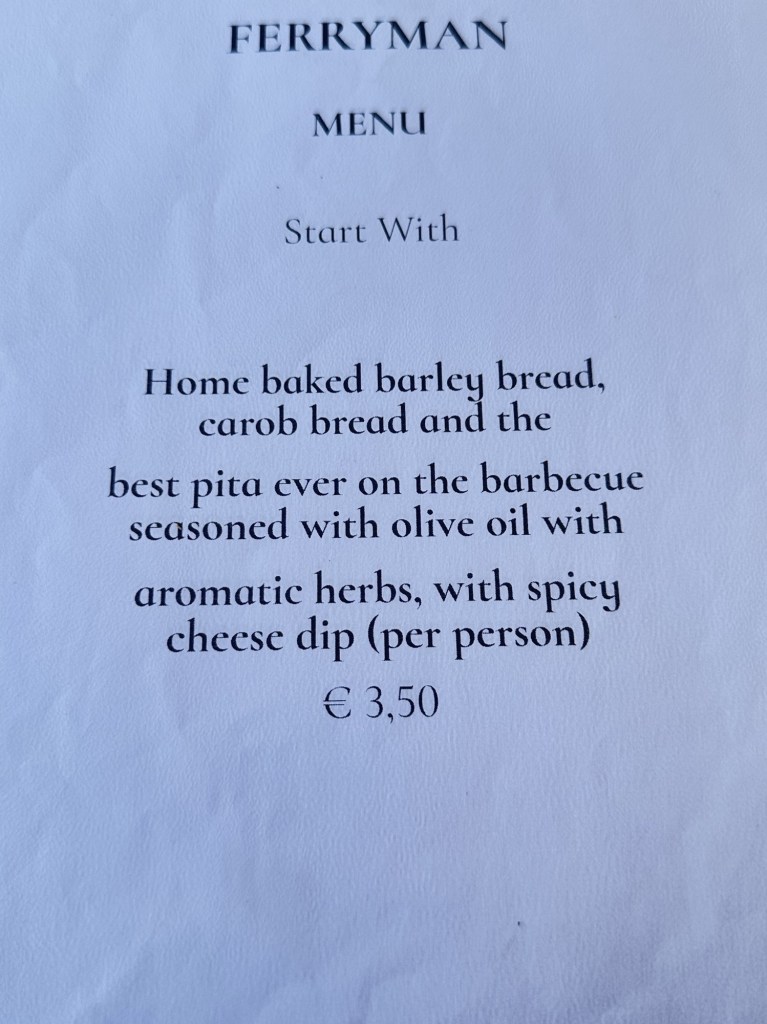

We enjoy our rooms and enjoy dinner a Ferryman Taverna (https://ferryman.gr/). Ferryman Taverna is charmingly perched right at the water’s edge in Schisma, just outside Elounda on the Gulf of Elounda. The restaurant’s stone-built terraces and shaded pergolas offer uninterrupted views of the sea, framed by boats gently bobbing nearby and distant mountains beyond. The warm, unpretentious atmosphere: tables with crisp linens, rustic wooden chairs, olive trees and palms overhead, and lanterns glowing in the evenings. The owner, Ak, is a big presence. Here I have the best that I’ve ever had.

The food so good and the atmosphere is so tranquil that I actually forgot to take pictures, except for some starts and dessert. I asked AK what the name of the dessert was, and he said it had no name. It was something his grandmother used to make. Perfect!